Webshop

My page

Yogurt

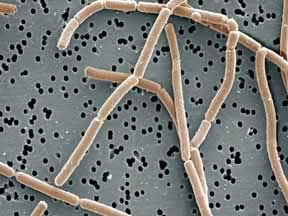

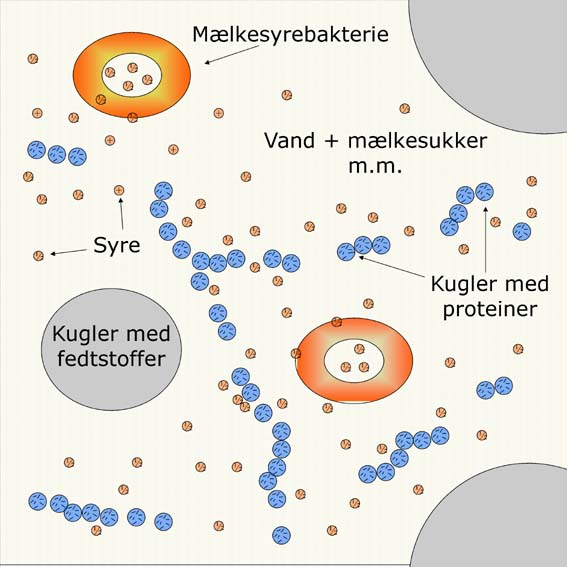

What is Yogurt?Making yogurts is an old tradition believed to originate from Central Asia and that is why you will sometimes hear it spoken of as “the Bulgarian’s drink”, even today. It was not until the early part of the 20th century the tradition won fame across the world as Russian biologist Ilyich Mekhnikov praised yogurt as the means to a long healthy life. Yogurts and other fermented dairy products is a result of lactic acid bacteria fermenting the milk by converting lactose (milk sugars) in the milk into lactic acid and hence, acidifying the milk. As these beneficial bacteria feed on lactose, lactic acid levels raise coherently and the drop in pH make it increasingly hard for the proteins to stay in solution. As a result, the proteins begin to cluster together, form bonds and tangle up in masses which is what appears as a thickening of the milk. Storebought milk has almost always been pasteurized (heat processed) with the purpose of killing off any harmful bacteria but the process kills off beneficial lactic acid bacteria too, and therefore they must be re-introduced to the milk to be able to make yogurt from it. Applying a culture with lactic acid bacteria will promote correct fermentation and enhance the development of palatable flavors. The class of lactic acid bacteria that are used to make yogurts from are thermophilic, meaning they are heat-loving species that thrives optimally betweeen 30°C and 45°C. The species that are most commonly used are Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Streptococcus thermophillus, Lactobacillus lactis and Lactobacillus helveticus. The difference between making yogurt and soured milk is only the mix of lactic acid bacteria we use to ferment the milk. Lactic acid bacteria for soured milk must be mesophilic, which simmply refers to a class of bacteria that prefer lower temperatures and thrive best around room temperature. Soured milk can therefore be made simply by leaving the milk to ferment somewhere in the house with a steady room temperature. Yogurt can be made in the exact same way if you can find a place in you house that provides a constant 42°C which is the optimum fermentation temperature for yogurts. If your house does not provide the optimal temperature to make yogurts anywhere, you can use an oven or an electrical yogurt maker to ensures a constant temperature thoughout the fermentation process. Or simply, do it the old fashoin way by heating the milk to 42°C, add a starter culture and wrap the pot in a warm thick blanket. Place the whole thing somewhere where it will will keep warm for up to 12 hours - a thermobox is often a good choice. |

Soured milk

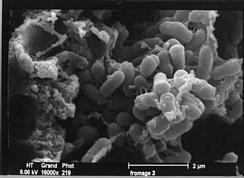

What is Soured milk?When milk is left at room temperature, natural occurring bacteria begin to develop and grow rapidly in a process of converting milk sugars (lactose) into lactic acid. Buildup of acid is what causes the well-known sourness in milk after a little while. - The bacteria behind this process are lactic acid bacteria – When lactic acid builds, acidity increases and pH levels drop making it increasingly hard for the proteins to stay in solution. This will cause the milk to coagulate and thicken and the outcome is what we know as soured milk. Soured milk is usually made from milk only – if you use cream instead of milk, the outcome will be a crème fraiche (soured cream). Fermentation happens the same whether you use whole milk, skimmed or semi skimmed milk – all kinds ferment equally well, as they contain equal amounts of lactose and proteins. The only thing that differentiate them from one another is the fat content and since fats does not play any active role in the fermentation process - choose a milk with the fat content you prefer. Lactic acid bacteria are everywhere - in the air, on our skin, in our gut, on fruits and in vegetables – we cannot avoid them. If we leave milk uncovered, lactic acid bacteria from the air will soon make their way in to the milk and begin to develop, converting lactose into lactic acid. There is a vast variety of lactic acid bacteria species; some contributes with palatable flavors we like, others, not so much. They live alongside other species of bacteria and fungi that occur almost everywhere – all competing for their share of whatever milk you just left out for them to colonize. Such random and wild fermentation could potentially be making it less of a palatable experience. Even the milking process induce bacteria to the milk and this is the reason why milk is pasteurized, to avoid growth of any undesirable bacteria. Since milk pasteurization also kills off naturally occurring good lactic acid bacteria, we must re-culture the milk with these bacteria prior to fermentation. Culturing milk with particular species of bacteria ensures correct fermentation and palatable flavors. When we add lactic acid bacteria cultures, the bacteria species in them will rapidly outnumber any undesirable bacteria that may have found their way into the milk. Rapid rising levels of acidity from these bacteria will naturally inhibit the growth of competing bacteria not liking acidic conditions. This is the reason why soured milk can often be stored for quite some time and keep fresh. A batch of freshly made soured milk with the right combination lactic acid bacteria species can be perfectly all right to use as a culture for the next batch of soured milk. Simply take out a small portion, mix it in with the milk for the next batch - using approximately ½ cup of freshly made soured milk to 1 liter of milk. Leave the milk at room temperature for about 24 hours and another 12 hours in the refrigerator. Then it will be ready to enjoy! This process can be used repeatedly, over and over again. However, be aware that bacteria from the surrounding environment may also find its way to your preparation somewhere along the process. By repeating the process many times, you may risk other types of lactic acid bacteria takes the upper hand and influence the flavoring in an undesirable way. A balanced combination of lactic acid bacteria is often crucial for the flavor and for us like it. If the balance between them is significantly distorted, flavors can be too and you must start over by making a new batch of soured milk from scratch, using a balanced culture. Buttermilk contains the same types of lactic acid bacteria as soured milk, therefore small amounts of that can be used to culture a batch of soured milk. Alternatively, you can use freeze-dried starter cultures for making soured dairy products. These have been readily made with correct balance of bacteria that will bring out nice palatable flavors in your products. Take a pinch of freeze-dried culture, dissolve it in a small amount of water or milk, stir well and add that in to your large portion of milk. Then follow the procedure as described above (leave for 24 hours at room temperature, covered, and then another 12 hours in the refrigerator). Lactic acid bacteria in soured milk are mesophilic, a group of bacteria that thrives around room at temperatures between 15°C and 30°C. The most commonly used species are; Lactocossus lactis, Lactocossus diacetylactis and Lactocossus cremoris. We stock such a mix in our web shop. |

Soured cream

What is Soured cream / Creme fraiche?Soured cream is simply fermented cream. In the very same way milk can be fermented to soured milk or yogurt, cream can be fermented to soured cream. Soured cream can be prepared with various fat contents simply by diluting cream with milk before you start the fermentation process. Fat content in cream varies from country to country. He following applies to Denmark:

For more detailed information on milk fermentation, please read the information on Soured milk and Yogurt. |

Cultures

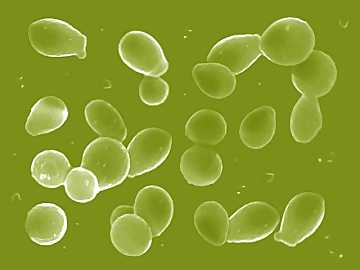

Cultures for Soured Milk, Yogurts, Kefirs and CheesesThe unique flavor in fermented produce and cheese is determined by a complex inter play between different enzymes, bacteria, fungus and milk content of sugars (lactose), proteins and fats. As enzymes, bacteria and fungus break down the milk ingredients, substances such as lactic acid, fatty acids, amino acids, aldehyde and ketones appear as a byproduct of this breakdown. This is what determines the complexity of flavors in cheeses. Below you will find a list of cultures commonly used for Soured Milk, Yogurts, Kefirs and Cheese.

List of cultures for making Soured Milk, Yogurts, Kefir and Cheese

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Yogurt chemistry

Fermented milk - ChemistryLeaving milk or cream at room temperature will cause naturally occurring bacteria within, to grow and develop as they digest and convert milk sugars (lactose) into lactic acid. Hence, lactic acid builds up and cause acidification as pH levels drops. - These bacteria are known as lactic acid bacteria – When lactic acid bacteria thrive, and increase in numbers, acidification follows which make it increasingly difficult for the proteins to stay in solution and cause them to tangle up and thicken the milk. The result is what we know to be soured milk. The same process transforms cream into soured cream. Yogurt develops in the exact same way, however differs by the type of bacterial species that drives the process and produce lactic acid. A more technical explanation on what happens when we create soured milk, soured cream and yogurt, follows below:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0/3

- Visitors: 1505446 - 1

0/3

- Visitors: 1505446 - 1